Cell and gene therapy future prospective

Cell and gene therapies represent revolutionary approaches in the field of medicine, offering promising avenues for treating a myriad of diseases at their core genetic and cellular levels. With rapid advancements in biotechnology and our deepening understanding of genetics, the future of healthcare is poised to be transformed by these innovative therapies. This essay explores the future prospects of cell and gene therapy, envisioning a landscape where personalised medicine becomes the norm, and previously untreatable conditions are conquered.

History

The history of cell and gene therapy is a fascinating journey marked by significant scientific breakthroughs, setbacks, and remarkable advancements. Here’s an overview of key milestones in the development of these innovative therapies:

Early Exploration (1970s-1980s):

In the 1970s, the groundwork for cell and gene therapy was laid through foundational discoveries and early experiments that set the stage for future advancements in the field. While the term “gene therapy” had not yet been coined, researchers began to explore the potential of manipulating genetic material for therapeutic purposes. Here are some notable events and developments from the 1970s that contributed to the history of cell and gene therapy,

Hamilton O. Smith and Kent W. Wilcox (1970) discovered the first restriction enzyme, HindII, while studying the bacterial immune system. This breakthrough paved the way for the manipulation and analysis of DNA, which would later become instrumental in genetic engineering techniques used in gene therapy. In 1971, Werner Arber, Daniel Nathans, and Hamilton O. Smith independently isolated the first restriction enzyme, HindII (later renamed HindIII), from the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae. This enzyme could specifically cut DNA at particular sequences, enabling scientists to manipulate DNA for various applications, including gene cloning and sequencing.

Arthur Kornberg and colleagues discovered DNA ligase in 1971, an enzyme capable of joining together DNA fragments. DNA ligase played a crucial role in early genetic engineering experiments by allowing researchers to insert foreign DNA into plasmids, a key step in recombinant DNA technology.

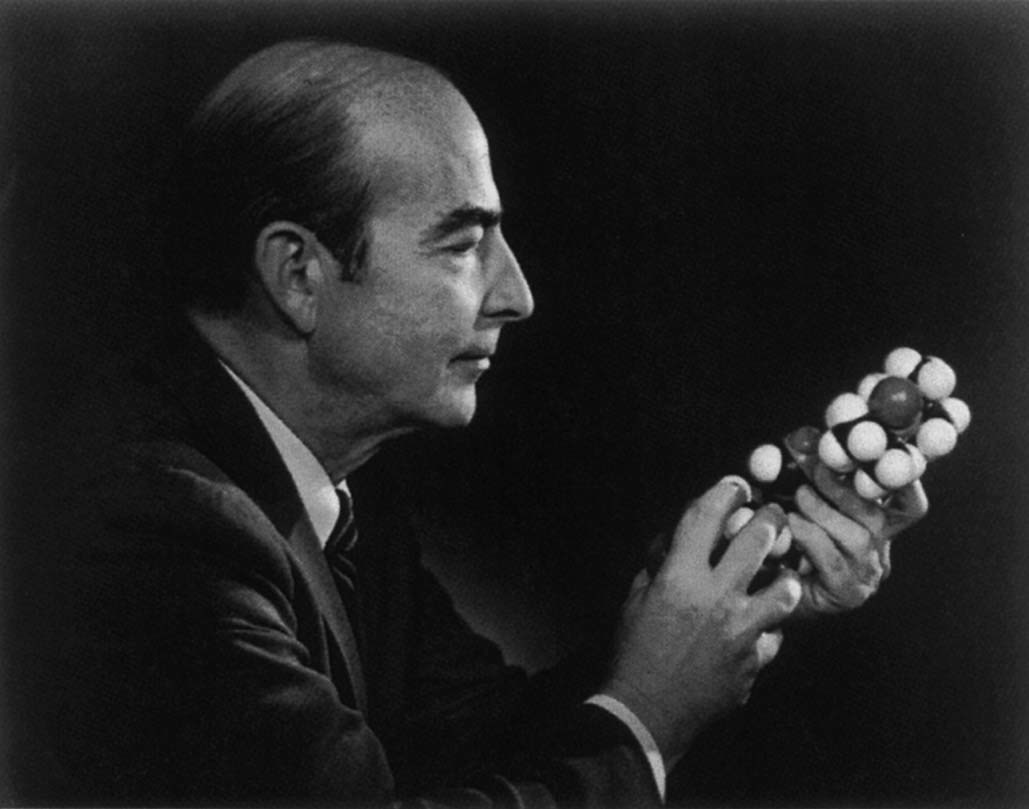

In 1972, Theodore Friedmann and Richard Roblin published a seminal paper in the journal Science titled “Gene Therapy for Human Genetic Disease?” In this paper, they proposed the concept of using genetic material to treat inherited diseases, laying the theoretical foundation for gene therapy. The development of recombinant DNA technology by researchers like Paul Berg who successfully combined DNA from two different organisms, and seminal work by Stanley Cohen, and Herbert Boyer in the early 1970s paved the way for gene cloning and the creation of genetically engineered organisms, laying the groundwork for future gene therapy approaches.

The United Kingdom also played a significant role in the early development of cell and gene therapy, particularly through pioneering research and scientific contributions that laid the groundwork for future advancements in the field In 1973, the University of Edinburgh hosted the landmark Gordon Conference on Nucleic Acids, where scientists discussed recent advances in molecular genetics, including the emerging field of recombinant DNA technology. Scientists like Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp at the University of Cambridge made key discoveries related to the splicing of RNA, which would later have implications for gene therapy approaches targeting genetic diseases.

As genetic research progressed, researched in the UK started the, discussions about the ethical implications of genetic engineering and potential risks associated with gene therapy interventions began to emerge, laying the groundwork for the establishment of ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks in subsequent decades.

The first gene therapy trial was conducted in 1980 by Martin Cline, who attempted to treat a patient with a genetic blood disorder called beta-thalassemia using genetically modified cells. Although the trial was unsuccessful, it paved the way for future research in the field.

While the 1970s primarily laid the groundwork for the field of gene therapy through foundational discoveries and theoretical proposals, it wasn’t until the following decades that experimental research and clinical trials began in earnest, leading to the development of the first gene therapy techniques and treatments.

Development of Viral Vectors (1980s-1990s):

During the 1980s, significant progress was made in the field of cell and gene therapy, laying the foundation for future clinical applications and advancements. Here are some key events and developments from that decade:

The development of viral vectors, such as retroviruses and adenoviruses, revolutionised gene therapy by providing efficient delivery systems for introducing therapeutic genes into target cells. Retroviruses, such as murine leukemia virus (MLV), were modified to serve as vectors capable of efficiently delivering therapeutic genes into target cells. These advancements paved the way for future gene therapy trials using viral vectors. Also, the term “gene therapy” was first coined in the 1980s to describe the concept of using genetic material to treat or cure diseases. Scientists and clinicians began to recognize the potential of gene therapy as a novel approach to treating genetic disorders, cancer, and other diseases at their root genetic causes.

Furthermore, in 1980s, researchers achieved significant breakthroughs in the creation of transgenic animals, which carried foreign genes deliberately inserted into their genomes. These genetically modified animals served as valuable models for studying gene function, disease mechanisms, and potential gene therapy approaches. As gene therapy research progressed, ethical and regulatory considerations became increasingly important. Scientists and policymakers engaged in discussions about the potential risks and benefits of gene therapy, as well as the ethical implications of manipulating human genetic material. These discussions laid the groundwork for the development of ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks governing gene therapy research and clinical trials.

While PCR was invented in the United States in the 1980s by Kary Mullis, its widespread adoption and further refinement involved contributions from scientists worldwide, including those from the UK. British researchers played important roles in optimising PCR protocols, developing new PCR reagents, and applying PCR techniques to various fields of research. The development of PCR significantly facilitated gene cloning and amplification efforts. British scientists were instrumental in the development of plasmid cloning vectors, which are circular DNA molecules that can replicate independently of the host genome. Plasmids served as essential tools for cloning and amplifying genes of interest. Research groups led by scientists like Sydney Brenner and Richard Durbin at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge contributed to the development of plasmid cloning vectors.

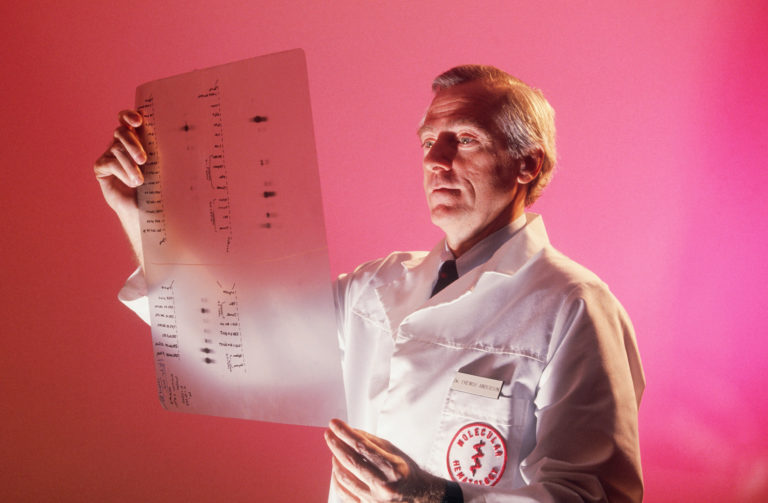

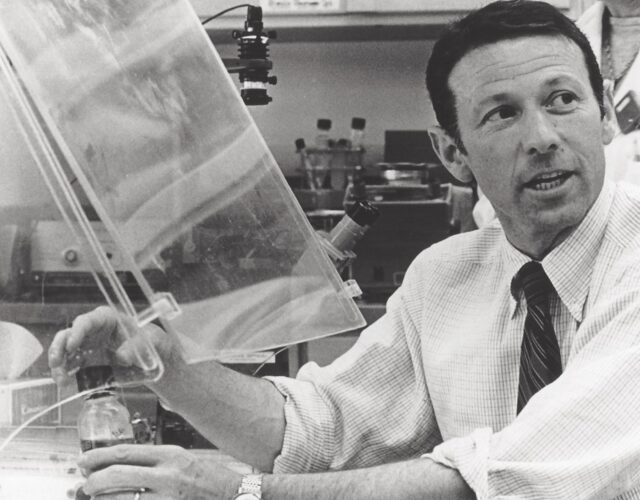

In 1990, the first successful gene therapy trial was reported by W. French Anderson and his collaborative team of British researchers, who treated a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) using a retroviral vector to deliver a functional copy of the defective gene.

George Dickson, a molecular biologist, conducted research in the 1980s that contributed to the development of gene therapy strategies for muscular dystrophy. His work focused on the delivery of therapeutic genes to muscle cells using viral vectors, laying the groundwork for future preclinical and clinical studies in the field.

Overall, the 1980s were a formative period in the history of cell and gene therapy, marked by pioneering research, technological advancements, and the birth of a new field aimed at harnessing the power of genetics to treat human diseases. While significant challenges remained, including safety concerns and technical limitations, the groundwork laid during this decade paved the way for future progress and clinical applications in gene therapy.